Sidney Jhingran, a reader and student from the University of Toronto, shares this article he first contributed for his campus newspaper.

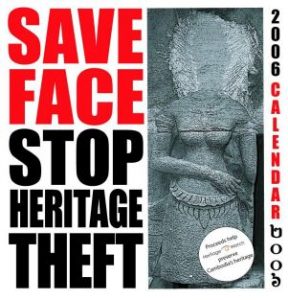

Cambodia’s Looting Crisis: The Illicit Trade in Khmer Antiquities

Those concerned about the state of Cambodia’s cultural heritage have been closely following the ongoing legal debate between the acclaimed auction house Sotheby’s on the one hand and the government of Cambodia (receiving support from the United States) on the other. The dispute revolves around Sotheby’s planned sale of a tenth-century Khmer statue, which was allegedly looted from the Prasat Chen temple at Koh Ker in the late 1960s or early 1970s (see here, here, and here for accounts of story—see here for a related case against the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

What many commentators have failed to address in regards to Sotheby’s intent to sell the statue and Cambodia’s request for its repatriation is that this recent confrontation is part of a much deeper, more structural crisis – a crisis of desecration and looting which has plagued Cambodia since the 1970s. It is a crisis engendered by the calamitous forces of the demand-driven antiquities trade, which has reached uncontrollable proportions on a global scale. Cambodia is particularly hard-hit by these forces, and the damage is staggering.

There are two types of heritage looting that occur in Cambodia. The first is the systematic desecration of historic temples, where statues, reliefs, lintels, etc. are uprooted or defaced by organized paramilitary groups and mobilized quickly across borders. Once the cultural objects are secure in a major antiquities transit hub, like Bangkok, they may be sold legitimately in antique shops or are shipped abroad (predominantly to the U.S.A and Europe) to be acquired by museums, auction houses, or private collectors. This type of looting has been endemic since the 1970s, when the calamities of the civil war and the Khmer Rouge regime, in addition to a heightened demand for antiquities on the international art market, made the plunder of temples a lucrative source of wealth. Though political stability slowly emerged in the 1990’s, the desecration of Cambodia’s thousands of temples, scattered across the countryside, accelerated at an alarming rate. While the Greater Angkor region in Siem Reap was granted privileged protection by UNESCO in the early 1990s, other large complexes, such as Banteay Chhmar, Banteay Trop, Koh Ker, and Prasat Preah Kahn of Kampong Svay, were systematically plundered by what are considered professional, highly organized, paramilitary organisations. For example, in 1999, a few hundred Cambodian soldiers, motivated by complicit and corrupt military officials who in turn had a “contract” with Thai dealers in Bangkok, entered the isolated temple complex of Bantaey Chhmar and proceeded to remove sculptures, lintels, reliefs and even an entire 400 square-metre decorated wall segment, and attempted to mobilize these by trucks across the Thai border. Though in this instance the trafficking was circumvented, most illicitly removed Khmer antiquities silently fade into the international art market. Tess Davis has estimated that between 1988 and 2005, 80% of around 345 Khmer sculptures and reliefs auctioned off at Sotheby’s in New York (most selling for thousands, some even over a million, dollars), were listed without provenance and thus were almost certainly looted. To this date, around 98% of Cambodia’s historic temples have, to a greater or lesser extent, fallen victim to the illicit trade in Khmer antiquities.

(Source: http://www.devata.org/2009/02/death-of-an-angel-how-antiquities-theft-destroys-cambodias-pastand-future/)

(Source: http://www.devata.org/2010/12/banteay-chhmar-working-to-save-another-angkor-wat/)

The second type of looting that occurs in Cambodia is the illegal excavation of archaeological sites, many of which are undocumented. In these cases, the looters are not paramilitary gangs but rather groups of impoverished rural workers seeking to supplement their incomes by scouring prehistoric cemeteries in search of the rich grave goods – carnelian, agate, and glass beads, pottery, bronze and iron artefacts– that are in demand both within the busy provincial markets of Southeast Asia as well as on the international art market. The large-scale looting of archaeological sites in Cambodia is a phenomenon which has skyrocketed since 1999, when the late Iron Age site of Phum Snay, which is considered one of the largest, and archaeologically richest, prehistoric cemeteries in Southeast Asia, was, according to Heritage Watch, “decimated by looters seeking its rich grave offerings.” It is estimated that 90% of the site had its context obliterated. Other incidences, such as the rapacious looting of Wat Jas in 2005 confirm that clandestine excavation of prehistoric sites has become a serious problem, equally as worrisome as the pillaging of historic temples. Iron Age jewellery and bronze artefacts are available by the bucketful in the markets of Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, and Bangkok.

(Source: http://www.otago.ac.nz/Anthropology/Angkor/-snay.html)

(Source: https://www.southeastasianarchaeology.com/2011/03/11/special-repatriation-cambodian-artefacts/)

There is an overarching legal framework which surrounds the Cambodian government’s struggle to stem the pillage of its cultural heritage. In 1996, the Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage was implemented to make explicit national ownership as well as “to protect national cultural heritage and cultural property in general against illegal destruction, modification, alteration, excavation, alienation, exportation, and importation.” In addition to this important national law, Cambodia has ratified both the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property and the 1995 Unidroit Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. These international conventions provide the principal means through which signatory states can cooperate in an effort combat the illicit trade in antiquities and thus diminish the loss of cultural heritage globally. Beyond legislative measures, Cambodia has also entered a bilateral agreement with the United States (a destination market with particularly high demand) meant to stem the flow of antiquities into U.S by asserting that the import of Khmer antiquities without a valid export license issued by the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts in Phnom Penh is prohibited. The Cambodian government has also reached a border agreement with Thailand (which is the main trafficking route for Khmer antiquities) which similarly is intended to enforce more stringent illicit trafficking control measures. It has been demonstrated that this proactive stance by the Cambodian government has led to some positive results, one of the most obvious being the restitution of a number of Khmer antiquities that had been smuggled out of the country over the course of the last three decades (the current negotiations with Sotheby’s and the Met are part of this pattern). Furthermore, Tess Davis has suggested that as a result of Cambodia-U.S bilateral agreement, fewer unprovenanced cultural objects have surfaced on the American art market. An important and welcome recent development on the legislative front is the creation of DHARMA (the Database of Historical and Archaeological Regulations for the Management of Antiquities), created to ensure that “lawyers, archaeologists, law enforcement officers, government officials, and collectors will have easy access to current national and international legislation affecting the management of heritage resources.” (see here for more details).

That being said, it is clear that the looting and decimation of Cambodia’s cultural heritage continues. In fact, there is evidence that the antiquities trade is just driven further underground as dealers and middlemen are forced to find ways around legal barriers. For example, while the border agreement with Thailand has resulted in a decrease in the frequency of seizures, it appears that the movement of antiquities, rather than being circumscribed, is merely shifting from Thailand to other transit hubs, particularly Singapore and Hong Kong. The fact that the market has adapted and is shifting course rather than being diminished indicates that legislative and political “barriers” to stem looting cannot be completely effective. Simply put, the reason why these barriers have been largely ineffective is because the underlying enabling factors which engender and sustain Cambodia’s looting crisis remain in place. These enabling factors include societal afflictions such as widespread corruption, rural poverty, and a lack of economic infrastructure to provide alternatives to illicit trafficking. Cambodia’s geopolitical position in Southeast Asia, particularly its proximity to Thailand, has also played a major role in aiding the development of industrial scale pillaging since the 1970s. Furthermore, the isolation and inaccessibility of many of Cambodia’s historic temples has rendered them incapable of being monitored to even a fraction of the degree witnessed at Angkor. Accessibility and site monitoring are lacking, and the limited incentive by the government to provide these imperatives continues to be a contributing factor to Cambodia’s vulnerability as a victim of antiquities theft. With undocumented prehistoric sites the situation is equally as problematic. There is hardly any deterrent, neither strong legislation nor high security, which will protect these sites and the fact that they are undocumented and located deep in the countryside makes them highly susceptible to looting. To many, the most significant enabling factor leading to widespread pillage is international demand. The buyers of Khmer antiquities, whether they are wealthy art dealers, museums, auction houses, private collectors, or tourists, provide the financial stimulus for the illicit antiquities market and legitimize the economic value of Cambodia’s cultural heritage. As such, buyers are directly and explicitly tied to the destruction of Cambodia’s historic and prehistoric patrimony.

But there is some good news. In 2003, archaeologist Dougald O’Reilly founded Heritage Watch, an NGO dedicated entirely to the preservation of Cambodia’s rich heritage. Heritage Watch applies an integrative approach which seeks to undermine the Khmer antiquities market while simultaneously trying to abolish the enabling factors that sustain its perpetuation. Essentially, the goal of the initiative is to reduce the supply and demand of Khmer antiquities and archaeological resources. This is tackled by implementing a number of strategies focused on different aspects of the crisis: social marketing to raise public awareness; sustainable tourism to facilitate rural poverty alleviation and accessibility; collaboration with the Cambodian government as well as the governments of transit and destination markets to strengthen laws; studying trends in the trade network; and organizing rescue excavations and surveys. I encourage everyone to visit Heritage Watch’s website (http://www.heritagewatchinternational.org/) to see past as well as current and future projects.

The laudable efforts of Heritage Watch have already made a significant contribution to the well-being of Khmer cultural heritage, and projects underway are equally as promising. Nonetheless, the looting continues. Concerted international action is needed, demand in buyer countries needs to be reduced, and socioeconomic conditions in Cambodia need to improve. There is no doubt that completely stemming the trade in Khmer antiquities and the plunder of archaeological sites will require structural changes and shifts in moralities that take years to develop. Significant steps are being taken in the right direction, and it is important that this path is nurtured by all who have an appreciation for Khmer culture because, as Tess Davis reminds us, “when archaeological sites are looted, the history of many is lost for the pleasure of a few.”