via PLoSOne: A new Open Access paper by Shipton et al. about the archaeology of Obi Island in northern Maluku, revealing prehistoric habitation between 18,000-10,000 years ago.

The first excavations on Obi Island, north-east Wallacea, reveal three phases of occupation beginning in the terminal Pleistocene. Ground shell artefacts appear at the end of the terminal Pleistocene, the earliest examples in Wallacea. In the subsequent early Holocene occupation phase, ground stone axe flakes appear, which are again the earliest examples in Wallacea. Ground axes were likely instrumental to subsistence in Obi’s dense tropical forest. From ~8000 BP there was a hiatus lasting several millennia, perhaps because increased precipitation and forest density made the sites inhospitable. The site was reoccupied in the Metal Age, with this third phase including quadrangular ground stone artefacts, as well as pottery and pigs; reflecting Austronesian influences. Greater connectivity at this time is also indicated by an Oliva shell bead tradition that occurs in southern Wallacea and an exotic obsidian artefact. The emergence of ground axes on Obi is an independent example of a broader pattern of intensification at the Pleistocene-Holocene transition in Wallacea and New Guinea, evincing human innovation in response to rapid environmental change.

Source: Early ground axe technology in Wallacea: The first excavations on Obi Island

See also:

Stone tools from a remote cave reveal how island-hopping humans made a living in the jungle millennia ago

Prehistoric axes and beads found in caves on a remote Indonesian island suggest this was a crucial staging post for seafaring people who lived in this region as the last ice age was coming to an end.

Our discoveries, published today in PLOS ONE, suggest humans arrived on the tropical island of Obi at least 18,000 years ago, successfully making a living there for at least the next 10,000 years.

It also provides the first direct archaeological evidence to support the idea these islands were crucial for humans’ island-hopping migration through this region millennia ago.

In early April 2019, we and our colleagues in Indonesia became the first archaeologists to explore Obi, in Indonesia’s Maluku Utara province.

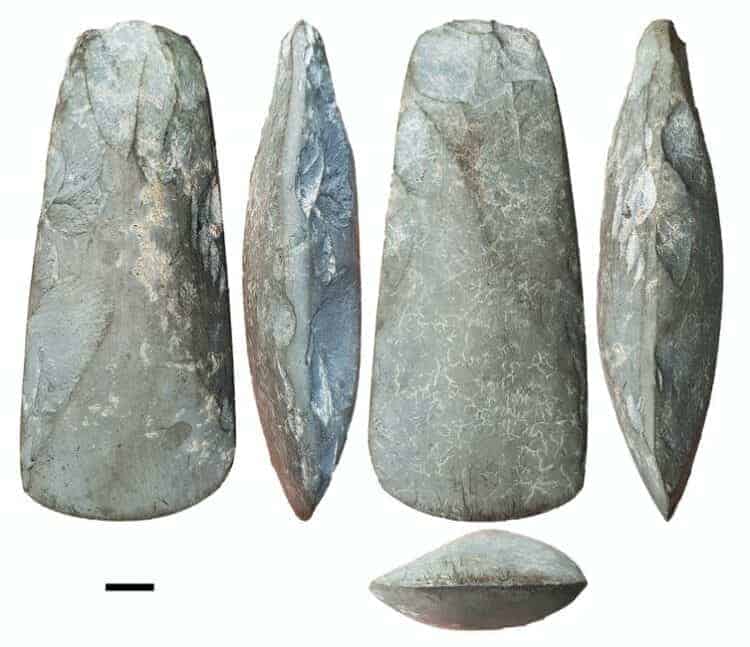

We found the oldest example from east Indonesia of edge-ground axes, made by grinding a piece of stone to a sharp blade against a rough material such as sandstone. These were likely used for clearing the forest and making dugout canoes.

Our discoveries suggest the prehistoric people who lived on Obi were adept on both land and sea, hunting in the dense rainforest, foraging by the sea, and possibly even making canoes for voyaging between islands.

Our research is part of a project to learn more about how people first dispersed from mainland Asia, through the Indonesian archipelago and into Sahul, the prehistoric continent that once connected Australia and New Guinea.

An island stepping-stone

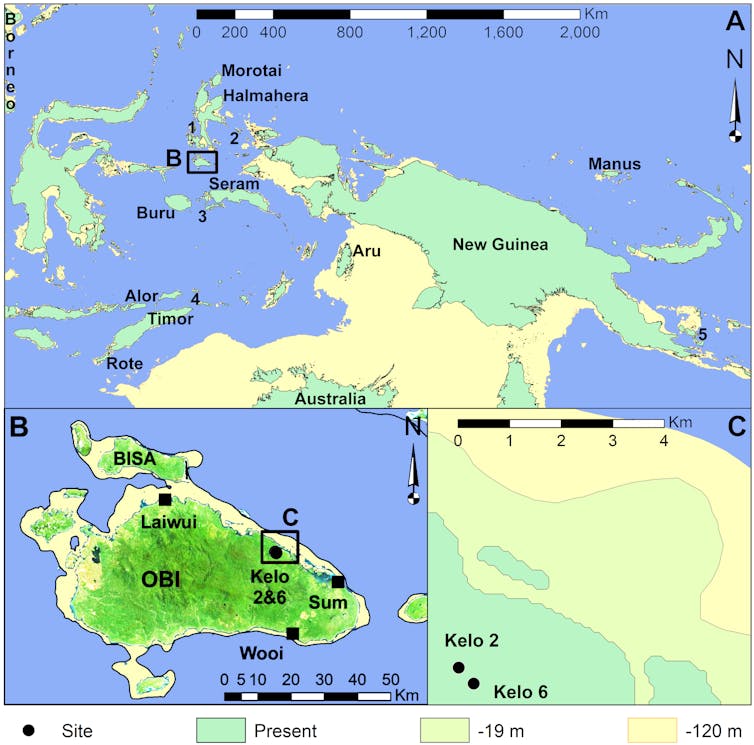

Recent models by CABAH researchers identified the collection of small islands in northeast Indonesia – and Obi in particular – as the most likely “stepping-stones” used by humans on their very first journey east towards northern Sahul (modern-day New Guinea), about 65,000-50,000 years ago.

Migrating through this region, which is named Wallacea after the explorer and naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, would have required multiple sea crossings. This enormous archipelago thus has a unique significance in human history, as the region where people first set out on deliberate long sea voyages.

Our earlier research suggested the northern Wallacean islands, including Obi, would have offered the easiest migration route. But to back this theory, we need archaeological evidence for humans living in this remote area in the ancient past. So we travelled to Obi to look for cave sites that might reveal evidence of early occupation.

Read more: Island-hopping study shows the most likely route the first people took to Australia

Tools and treasure

We found two rock shelter sites, just inland from the village of Kelo on Obi’s northern coast, that were suitable for excavation. With the permission and help of the local people of Kelo, we dug a small test excavation in each shelter.

We found numberous artefacts including fragments of edge-ground axes, some dating to about 14,000 years ago. The earliest ground axes at Kelo were made using clam shells. Axes made from shells have also been found elsewhere in this region from roughly the same time, including on the nearby island of Gebe to the northeast. Traditionally, they were used by people in the region for the construction of dugout canoes. It is highly likely that Obi’s axes were also used for making canoes, thus allowing these early peoples to maintain connections between communities on neighbouring islands.

The oldest cultural layers from the Kelo 6 site, containing a combination of shell and stone tool flakes, provided us with the earliest record for human occupation on Obi, dating back around 18,000 years. At this time the climate was drier and colder the today, and the island’s dense rainforests would likely have been much less impenetrable than they are now. Sea levels were about 120 metres lower, meaning Obi was a much larger island, encompassing what is today the separate island of Bisa, as well as several other small islands nearby.

Roughly 11,700 years ago, as the most recent ice age ended, the climate became significantly warmer and wetter, no doubt making Obi’s jungle much thicker. It is perhaps no coincidence this is the time we see the first evidence of axes made from stone rather than sea shells, likely in response to their increased, heavy-duty use for clearing and modification of the increasingly dense rainforest. While stone takes about twice as long to grind into an axe compared to shell, the harder material also keeps its sharp edge for longer as well.

Judging by the bones we found in the Kelo caves, people living there mainly hunted the Rothschild’s cuscus, a possum-like animal that still lives on Obi today. As the forest grew more dense, people probably used axes to clear patches of forest and make hunting easier.

Again, it’s probably no coincidence axes made of volcanic stone – which would have stayed sharp for longer, and are known to have been used for this purpose in New Guinea – first appearing in the archaeological record at around the time the climate was changing.

We also found obsidian, which must have been brought over from another island as there is no known source on Obi, and particular types of shell beads in the Kelo caves, similar to those previously found on islands in southern Wallacea. This again supports the idea that Obi islanders routinely travelled to other islands.

Moving out, or moving on?

Our excavations suggest people successfully lived at the Kelo caves for about 10,000 years. But then, about 8,000 years ago, both sites were abandoned.

Did the residents leave Obi completely, or move elsewhere on the island? Perhaps the jungle had grown so thick human axes (even stone ones!) were no longer a match for the dense undergrowth. Perhaps people simply moved to the coast and became mainly fishers rather than hunters.

Read more: An incredible journey: the first people to arrive in Australia came in large numbers, and on purpose

Whatever the reason, we have no evidence for use of the Kelo shelters after this time, until about 1,000 years ago, when they were reoccupied by people who had pottery and metal items. It seems likely, in view of Obi’s location in the middle of the Maluku “Spice Islands”, this final phase of occupation saw the Kelo shelters used by people involved in the historic spice trade.

We will hopefully find the answers to some of these questions when we return to Obi next year, COVID permitting, to excavate some coastal caves.![]()

Shimona Kealy, Postdoctoral Researcher, College of Asia & the Pacific, Australian National University and Sue O’Connor, Distinguished Professor, School of Culture, History & Language, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.